Linking the mind and body for better physical therapy

Nearly half of physical therapy patients are ages 65 and above. Older bodies often have unique needs for therapy, but they’re not necessarily treated with different approaches than younger patients. To get better results, all it might take is a pencil and paper.

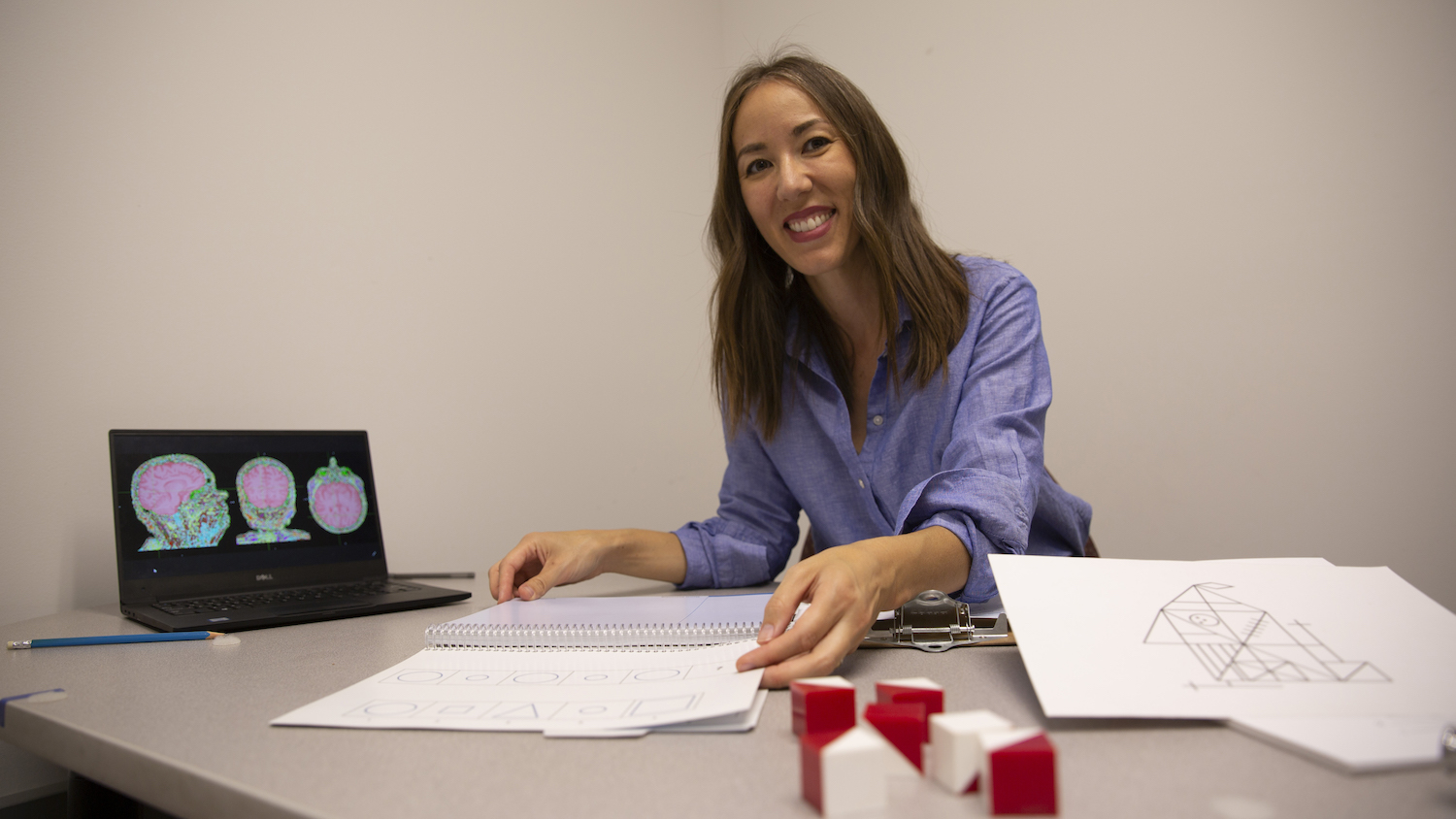

Sydney Schaefer, an assistant professor of biomedical engineering in the Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering at Arizona State University, is working toward developing more personalized solutions for neurorehabilitation (treatment for a nervous system injury) that are tailored to older patients. She and her research team are exploring inexpensive and easy-to-implement solutions similar to current practices.

“We use tools and assessments that are already being used by clinicians, but we are using them in non-traditional ways that could innovate standard care,” Schaefer says.

By identifying and testing a number of cognitive domains — memory, language and attention, for example — Schaefer and her team found visuospatial tests are the best predictors of success for physical therapy outcomes. These types of tests determine how well people can visually perceive objects and their features.

“We know that specific parts of the brain are involved in visuospatial function, and our hypothesis is that similar networks are critical for learning motor skills, which are fundamental to the rehabilitative process,” Schaefer says.

A common visuospatial test involves drawing the face of an analog clock and setting it to a particular time specified by a clinician or experimenter.

Schaefer and the research team are studying the use of pencil-and-paper tests, and sometimes computer-based tests, to evaluate older adults’ visuospatial skills. Questions include visualizing an object’s orientation, mentally rotating an object to a different orientation and recreating the shape of an object by drawing or building it, sometimes from memory.

The results the team has gotten so far suggest that clinicians focused on cognitive and physical rehabilitation can improve patient outcomes by communicating more with each other.

“In clinical care, motor and cognitive issues are often treated separately,” Schaefer says. “Neural circuitry may have more overlap than originally thought.”

Their research suggests that treating visuospatial deficits may have downstream effects on improving motor rehabilitation. Cognitive testing prior to motor rehabilitation can inform how patients should approach physical therapy to yield the best results.

The team was awarded a National Institutes of Health R03 grant, which supports two-year research projects to help develop larger-scale ideas.

Schaefer says the grant reviewers were particularly impressed by the significance of the work because “it has the potential to offer an inexpensive solution to a major problem in rehabilitation research and can alter how new clinical trials in stroke rehabilitation and other forms of motor skill training are implemented.”

Schaefer’s research team is using the grant to identify which visuospatial test is most predictive of skill learning in older adults, including older adults with a history of stroke, through the development of predictive cognitive algorithms and approaches that can enhance the success of physical therapy treatment.

The team is also developing low-cost tests that can be widely implemented in clinical and community-based settings.

“The simplicity of using existing clinical tests in the cognitive domain to better understand motor-based outcomes was viewed as novel,” Schaefer says.

She attributes much of the project’s success to the wealth of clinical partnerships available through the School of Biological and Health Systems Engineering, the accessibility of the ASU campus research space for working with older adults and the quality of graduate students the school recruits.

Her graduate student, Jennapher Lingo VanGilder, earned a National Institutes of Health Ruth L. Kirschstein Predoctoral Individual National Research Service Award Fellowship to support her neuroimaging work, which has contributed to the success of Schaefer’s research.

Going forward, Schaefer’s team is exploring additional therapeutic solutions and whether enhancing visuospatial function through neuromodulation can enhance skill learning.

Monique Clement

Communications specialist, Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering

(480) 727-1958 | [email protected]